Adnan Yahya

Adnan Yahya Essay

click the image to view

Adnan Yahya was a Palestinian artist born in 1960 to a family who, like many Palestinians in Amman, Jordan, can trace their ancestry back to Yafa. Jordan, being a fairly young country, was established in the early twentieth century by the British as a pressure valve to ease the waves of Palestinian refugees being forced from their homeland and relocated. Under the British Mandate of Palestine, colonial forces sought to make room for the influx of European migrants while supporting Zionist terrorism against the indigenous population of Palestine.

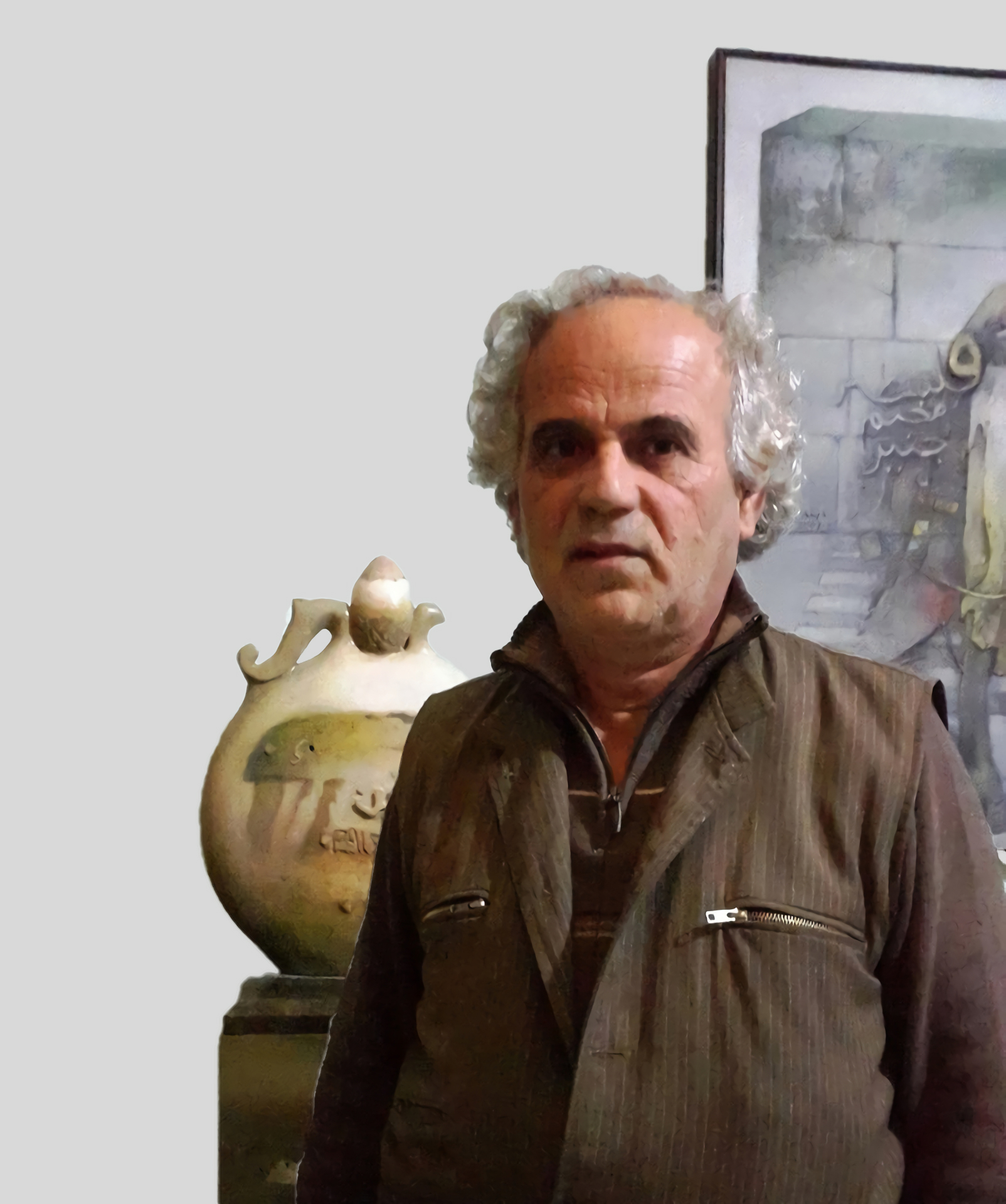

My first knowledge of Yahya as an artist was when I acquired the first of many of his paintings from the 2004 traveling exhibition Made in Palestine. Later upon a visit to Amman, Jordan in 2007, I was able to make his acquaintance by visiting his home in the Um-Al-Thawarah district of the city. After being introduced to every member of his very pleasant family, I was pleased to learn that two of his children are named after two historical Shi’ite religious figures, Hamza and Jaafar, while the other two are named Naji, after the cartoon artist and satirist Naji Al-Ali, and Omar, after a Sunni historical character. When asked about the names of his children he answered: “I have no divisive beliefs about Sunni and Shiites. The concept of division serves only the policy of colonization and that is what the West is trying to implant in the minds and hearts of the people around the Arab World, which is what we see happening at this moment in Iraq with the concept of “the Sunni Triangle.”

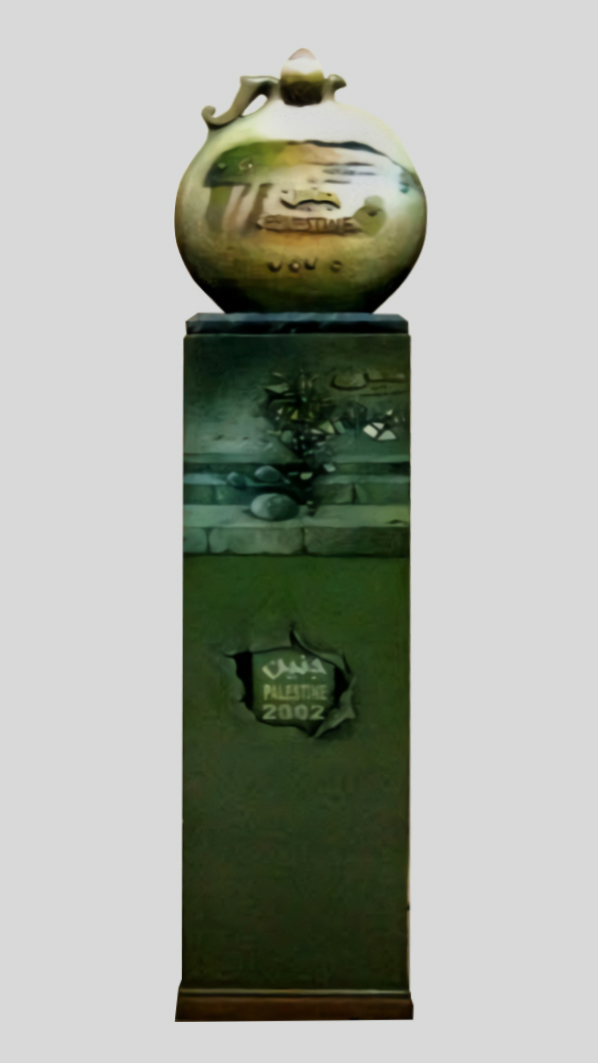

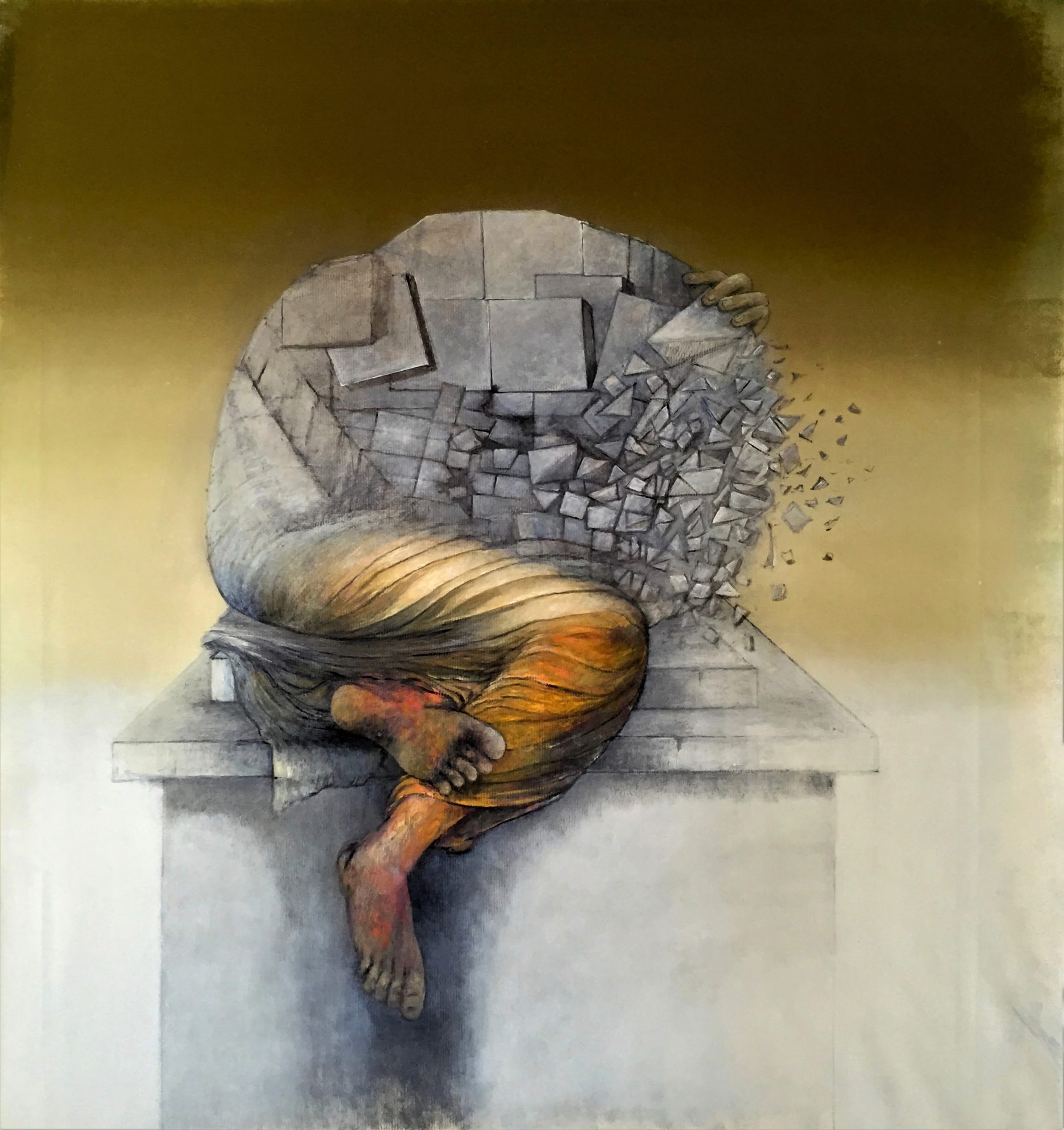

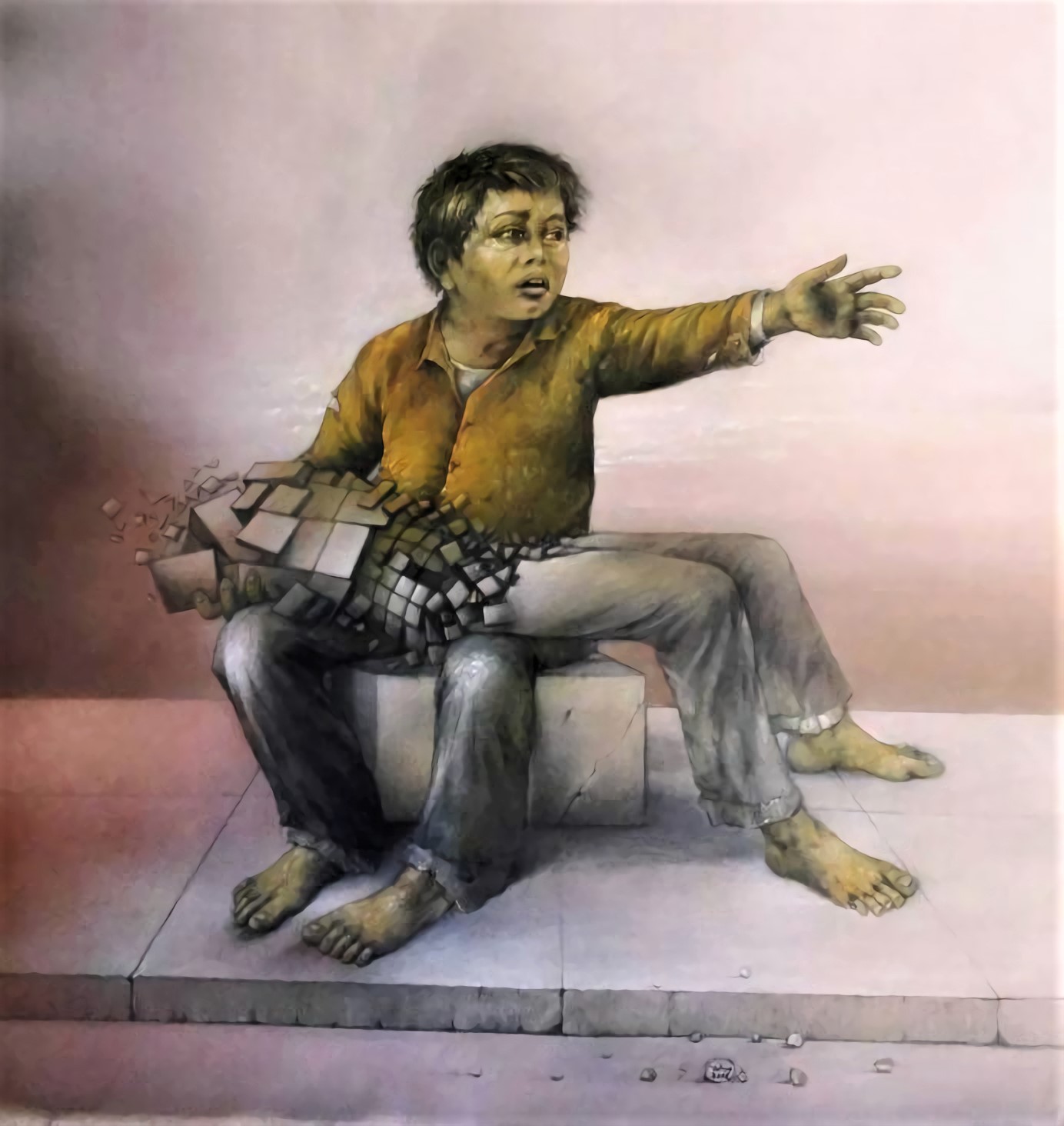

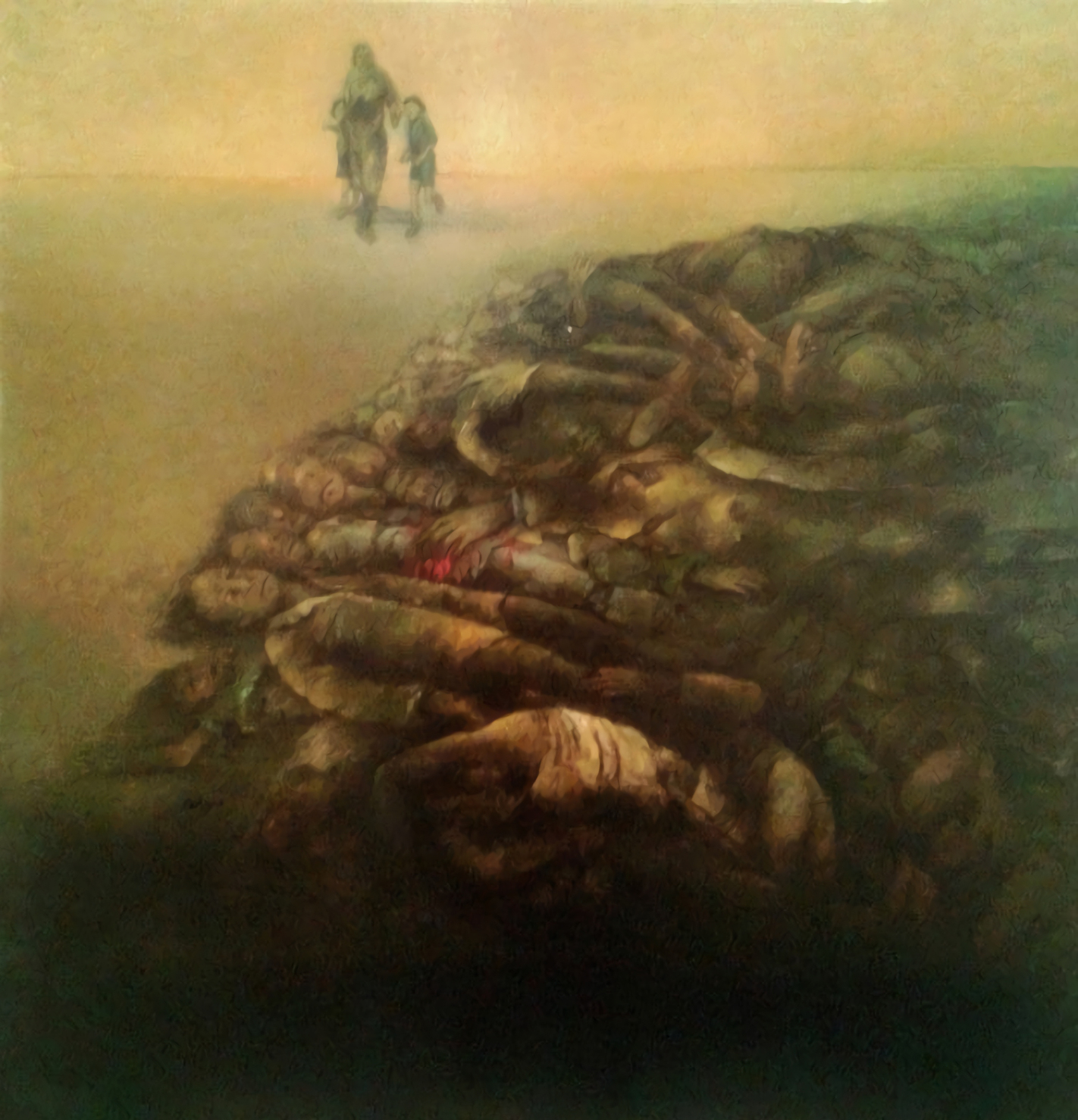

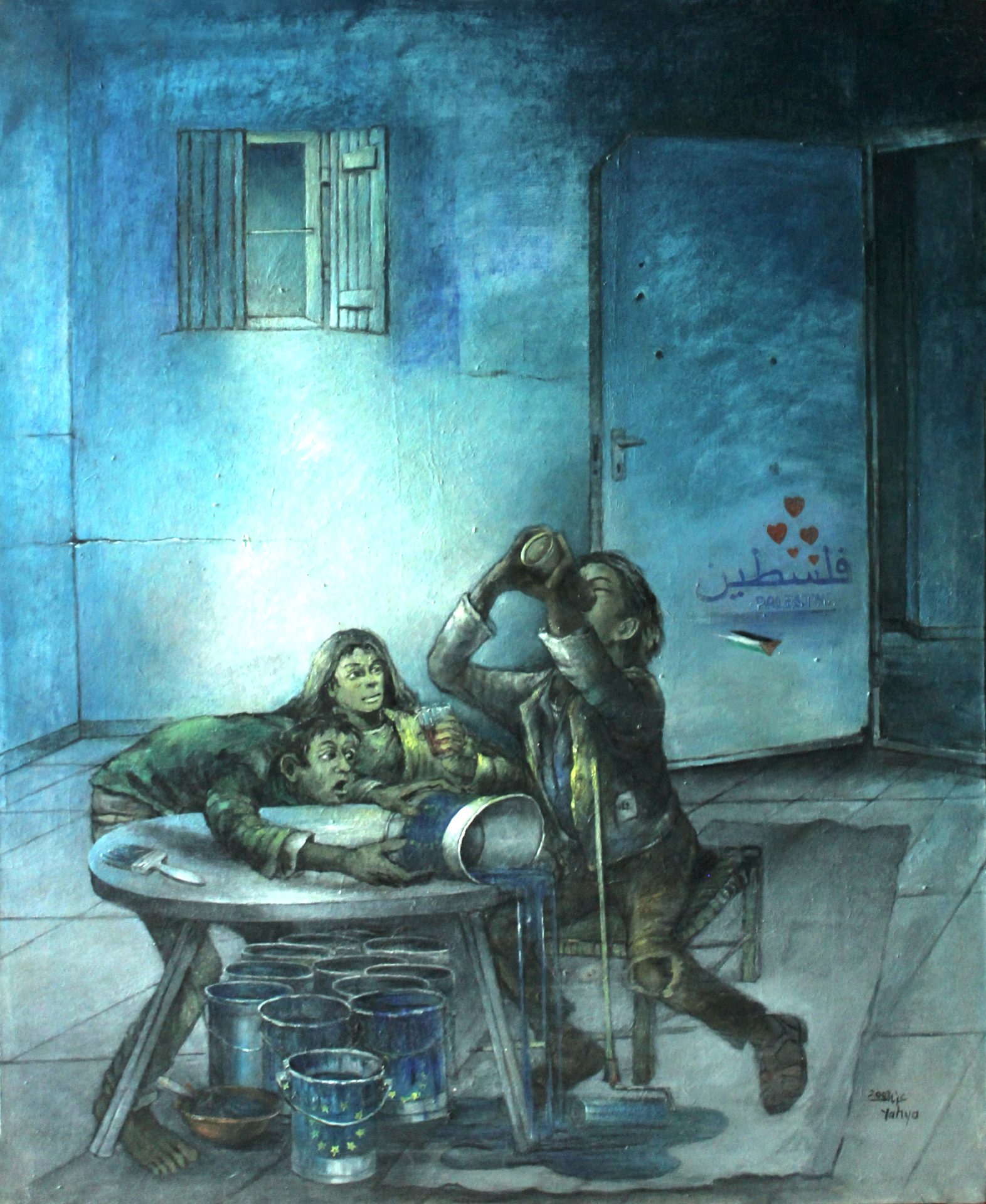

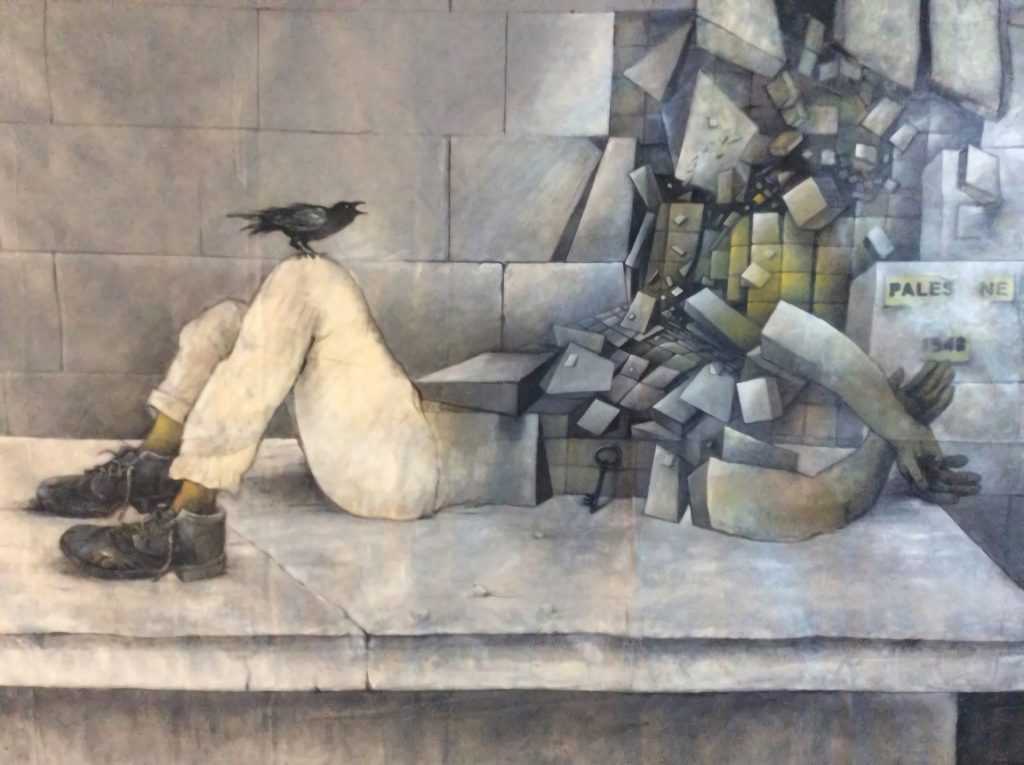

From close-up examination of his work, one cannot ignore that Adnan Yahya works much like an archivist who documents the history of his people through his paintings, sculptures, and ceramics. Undoubtedly, his is a new school of aesthetics that stands on its own, Yahya is distinct in artistic prowess and humanist thought.

Yahya treats his compositions with a post-Surrealist approach in which his subjects are magnified sculptures of deteriorating images of generals who represent the tyranny of “Super Powers” frozen in the past. For the artist, it is only logical to visualize power as “statuary” because every powerful leader strives to build a larger monument than the one before, immortalizing their earthly existence at the expense of their own people or others whom they have colonized. His use of insects, such as ants and cockroaches, as symbols of soldiers transporting death, destruction, and ruin from one place to another while disregarding human life present a clear condemnation of the military industrial complex and the societies that sustain it.

Naim Farhat (2022)

My first knowledge of Yahya as an artist was when I acquired the first of many of his paintings from the 2004 traveling exhibition Made in Palestine. Later upon a visit to Amman, Jordan in 2007, I was able to make his acquaintance by visiting his home in the Um-Al-Thawarah district of the city. After being introduced to every member of his very pleasant family, I was pleased to learn that two of his children are named after two historical Shi’ite religious figures, Hamza and Jaafar, while the other two are named Naji, after the cartoon artist and satirist Naji Al-Ali, and Omar, after a Sunni historical character. When asked about the names of his children he answered: “I have no divisive beliefs about Sunni and Shiites. The concept of division serves only the policy of colonization and that is what the West is trying to implant in the minds and hearts of the people around the Arab World, which is what we see happening at this moment in Iraq with the concept of “the Sunni Triangle.”

From close-up examination of his work, one cannot ignore that Adnan Yahya works much like an archivist who documents the history of his people through his paintings, sculptures, and ceramics. Undoubtedly, his is a new school of aesthetics that stands on its own, Yahya is distinct in artistic prowess and humanist thought.

Yahya treats his compositions with a post-Surrealist approach in which his subjects are magnified sculptures of deteriorating images of generals who represent the tyranny of “Super Powers” frozen in the past. For the artist, it is only logical to visualize power as “statuary” because every powerful leader strives to build a larger monument than the one before, immortalizing their earthly existence at the expense of their own people or others whom they have colonized. His use of insects, such as ants and cockroaches, as symbols of soldiers transporting death, destruction, and ruin from one place to another while disregarding human life present a clear condemnation of the military industrial complex and the societies that sustain it.

Naim Farhat (2022)